Revelation

The Christ

Outline

Contents

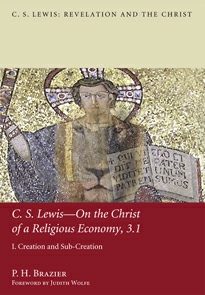

C. S. Lewis - On The Christ of a Religious Economy

I. CREATION AND SUB-CREATION

Part One

The Fall, Original Sin, and an Existential Crisis

Chapter 1 Creation and The Fall I: C. S. Lewis – A Doctrine of Creation

Chapter 2 Creation and The Fall II: Lewis’s “Augustinian” Account

Chapter 3 Creation and The Fall III: Innocence and Sin, Re-Interpreted

Chapter 4 Creation and The Fall IV: The Human Condition Before God

Part Two

Christ Revealed through Analogical Narrative

Chapter 5 Analogical and Symbolic Narratives I:

Narrative Theology, Supposition and Genre, Mythopoeic Theorizing–Imagining The Christ

Chapter 6 Analogical and Symbolic Narratives II:

Christology and Christlikeness – Hiddenness and Multiple Incarnations

Chapter 7 Analogical and Symbolic Narratives III:

Christology and Christlikeness – Trinitarian Considerations

Chapter 8 Analogical and Symbolic Narratives IV:

Salvation, Encounters and Judgement – the Work of the Aslan-Christ

Chapter 9 Analogical and Symbolic Narratives V:

Father Christmas in Narnia? – Intimations of Atonement and Salvation

C.S. Lewis: Revelation and the Christ, Book 3.1

C. S. Lewis – On The Christ of a Religious Economy

I. Creation and Sub-Creation

Part One The Fall, Original Sin, and an Existential Crisis

Part One (chapters 1–4) is about a fundamental component of Lewis’s apologetics and philosophical theology: “the Fall.” Lewis capitalizes the word to indicate the gravity of original sin: “the Fall” is therefore a proper noun. Speaking of the Fall immediately invokes a doctrine of creation: how and what were we created for? What does Lewis have to say about the creation? If we have fallen we are not as created. What is Lewis’s doctrine of creation – the universe created by and through the Christ? Lewis’s understanding of creation is spread across all of his works, he did not write a doctrine of creation, as such. However, we can draw this understanding together and systematize into four axioms and four theological principles, explicated in detail by what Lewis wrote and said.

The Fall is fundamental to Lewis’s orthodox theology.The Fall is a general term for a doctrine of original sin, based on the biblical story of Eve and Adam’s rebellion (Genesis 3). These chapters explore what place it has in Lewis’s theology generally, his Christology specifically: what exactly is a Christian theological anthropology and why is it relevant? What exactly does the Biblical story tell us, admittedly in metaphorical language, where humanity “eats” the fruit of the tree of good and evil? Much of Lewis’s doctrine of the Fall is derived from his reading of patristic theologians and philosophers – specifically Augustine’s de civitate Dei (The City of God). After examining the Biblical account (Genesis and Romans) we can explore Augustine’s doctrine of original sin – the Fall; likewise a specifically Roman Catholic (which influenced Lewis) catechetical understanding, and a doctrinal Anglican “article” from Lewis’s Church of England. What exactly is concupiscence and what role does it play in the 1600 year old Christian tradition that influences Lewis? The answers lies in what Lewis wrote about the Fall, and God’s atonement achieved through his sacrifice on the cross. Lewis’s account, and the theology we can read from it, invokes an important distinction between prelapsarian humanity and postlapsarian humanity, but also the concept of the Unfallen, that is, humanity before the Fall (but also the speculation with regard to other sentient species, other rational creatures, God may have created in the universe or other worlds, who have not Fallen: paradise retained). Lewis critically deconstructs a doctrine of total depravity, applying his training in logic, concluding that it cannot be so, or we would not be able to perceive it.

Lewis, like others, explores the story of the Fall, re-told, trying to work out what exactly happened to proto-humans, and what exactly is meant by the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Is the Fall merely a spiritual disease, or has it become physically embedded in us? To this end we can examine the retelling of the story of the Fall – variations on a theme – by Lewis, but also by such writers as Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, Thomas More, John Austin Baker, John Milton and William Golding. Lewis “retells” also in his novel Perelandra: a conscious, sentient, rational, creature, God-created, in another world, on another planet, is obedient and does not Fall: paradise retained. On the other hand Philip Pullman praises the Fall – it is a worthy price to pay for self-awareness, knowledge . . . and freedom from God? Sin and Sinners: acknowledging the Fall is one thing, but when the human predicament is to live with or without knowledge of original sin, what does Lewis make of the human condition and its propensity to sin? Lewis wrote often about human attempts to acknowledge sinfulness, in particular the relationship between holiness and an awareness of sin – in effect life in the shadow of the Christ. What does he tell us through Screwtape’s inverted understanding? What is the answer to the Fall, to original sin for Lewis? Christ is the answer, and Christ “is not wearied by our sins or our indifference” Christ is relentless in his “determination that we shall be cured of those sins, at whatever cost to us, at whatever cost to him.”

Speaking of the Fall immediately invokes a doctrine of creation: how and what were we created for? What does Lewis have to say about the creation. What is Lewis’s doctrine of creation – the universe created by and through the Christ. We have invoked the orthodox doctrine of original sin, based on the biblical story of Eve and Adam’s rebellion, however, how does it have manifold and far reaching effects on humanity? What is the human condition before God defined by? We are the corrupted creation, the rebel stood before its maker and judge. What is the backdrop of twentieth century theology that Lewis is reacting against – characterized by a form of neo-Pelagianism? Can science help or hinder in understanding the human condition and its manifold delusions given the use of reason in this rebellion? A refutation of “Liberal” scepticism lies in understanding the transmission of original sin, and how humanity is “true to type” (but not true to “form,” platonically we are not as we should be). God is good; and it is only through God’s overwhelming and overflowing goodness that we can have any hope of salvation out of our predicament. Lewis concluded his apologetic writing on sin by reasserting in the last year of his life natural, God-given, law, which defined human relations and behaviour, even if we failed to obey, to act out and be obedient. The Fall affects our ability to reason and to know, and to understand with any cogency and accuracy, which renders our attempts at the good flawed. So how does reason stand against revelation? What was Lewis’s understanding of reason in the light of his doctrine of the Fall.

Part Two Christ Revealed through Analogical Narrative

Therefore Part Two (Chapters 5–9) scrutinizes Lewis’s use of narrative—story—underpinned by doctrine to convey the truth of the Gospel. Lewis’s mission and work (as a pre-modern orthodox traditionalist) is a precursor, in many ways, to Postliberal theology, where the revelatory value of narrative, parable and metaphor is biblical. The precedent is scriptural: Jesus’s meeting with followers on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:25-27). Can we see Lewis’s analogical and symbolic narratives as a precursor of Postliberal, or Postmodern, Narrative Theology?—The Space Trilogy (1938–45), The Screwtape Letters (1942), The Great Divorce (1945), The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–56), and Till We Have Faces (1956) are, in many ways, parables and metaphors of the Kingdom of God. As such they are deeply scriptural; and in form structure they are influenced by Lewis’s doctrine of Christological prefigurement. Therefore we can look at how Lewis wrote his own Christian myths (symbolic theological narratives) to help people understand what had happened two thousand years ago, and how this relates to the human predicament and the truth of the Gospel where the method is analogical rather than allegorical. Lewis’s narratives and stories are implicitly theological and draw people into an understanding of God’s salvific purposes—a religious economy. The Space Trilogy and the Narniad are therefore a veiled understanding outside the Church.

Is Christ absent from The Great Divorce, is this a neo-Pelagian picture? Is this a picture of humanity trying to work out salvation for itself? Or is it one of prevenient grace? Therefore what is the relationship between Christ and the Holy Spirit in Lewis’s narratives—and therefore is there a sound Trinitarian basis to The Chronicles of Narnia? What images/word pictures does Lewis paint of Christ in Aslan, Ransom, etc., and how do the characters in these stories relate to Christ? What is the place of beauty in the revelation that is Aslan the lion? What does Lewis understand and present of Christlikeness? We need to decide what genre and source they are drawn from: what are these narratives of Lewis—fantasy, allegory? Lewis specifically denied any one-to-one correspondence; also, that there is no allegorical or hidden, meaning; furthermore they are not fantasy because of their theological content. They are “supposals.” That is analogy and metaphor: what if? The Narniad is a form of mythopoeic theorizing: what would happen if Christ was incarnated into another reality, dies and is resurrected for the salvation of the people there? Lewis commented that, “The Whole Narnian Story is about Christ.” What understanding of the Christ does Lewis present in his analogical and symbolic narratives—specifically, but not exclusively, in The Chronicles of Narnia? We can look at how Lewis wrote his own Christian myths, theologically cogent narratives, written in aim and objective, form and genre, like the North European Pagan myths that he justified, to a degree, through his doctrine of Christological prefigurement. What images/word pictures does Lewis paint of Christ in Aslan, Ransom, Psyche, etc., and how do the characters in these stories relate to the Christ event? What is the place of beauty in the revelation that is Aslan the lion? What does Lewis understand and present of Christlikeness? Christ is often veiled, hidden, in these narratives.

The question of multiple incarnations is raised by Lewis’s speculative suppositions. Is the incarnation, and therefore the cross and resurrection, unique? Can the Christ be incarnated human more than once in our reality, or perhaps somewhere else in our universe, in a distant galaxy, or another reality outside our universe? Lewis goes to the heart of the matter—there may be rational species, other than the human, who may be fallen, or unfallen. We may analyse Lewis on the question of multiple incarnations, but also contemporary theologians such as Brian Hebblethwaite and Oliver Crisp, and how all relate to Aquinas’s handling of the question. The relationship between Christ and the Holy Spirit in Lewis’s narratives is implicitly Trinitarian. Can we consider the Narniad orthodox? Why is there no apparent nativity, but theophanic appearances instead? We may consider what the Narniad tells us about the Holy Spirit’s mysterious actions within a religious economy. If, according to Lewis’s supposition, Aslan could be the form taken by the second person of the Trinity in another totally different and separate reality, and, if the salvation history in different disparate created realities converge the closer each gets to the issues at the heart of atonement and salvation, then we will examine what encounters Lewis wrote between God in Christ in Narnia and individual sentient creatures (human or otherwise)—both general and specific—and how these compare analogically with the salvation history and religious economy in our world for humanity. For example Shasta (The Horse and his Boy), likewise Emeth (The Last Battle), whose religio-political allegiances appear to condemn him, but he is saved, which illustrates the loving purposes of God. These encounters raise questions about the reality of God-given goodness outside of our religious egos, also the place of Lewis’s Platonism, but crucially about faith and works. Grace initiates; works respond. What is the nature of The Last Judgement in Narnia? What does this tell us about our fate? There is a clear assertion of God’s authority, but there is sometimes paradox. For example, the characters of Shift the Ape and Puzzle the Donkey, also what we may term, the neo-Kantian Feuerbachian dwarves (The Last Battle). what does this tell us about salvation for the Pagan and heathen, outside of the knowledge of Christ, as an exegesis, for Lewis, of Matthew 25 (The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats), but also Matthew 7:21 on those who do the will of God.

The inclusion of the character of Father Christmas by C. S. Lewis in The Chronicles of Narnia has consistently generated disapproval from numerous critics: what is a mythical person rooted in a uniquely this-world-religious-event doing in Narnia? We can demonstrate how Lewis’s genre of “supposal” operates as a Christological exposition and and as theologoumena by explaining the inclusion of Father Christmas. Lewis was right to include the character, and to retain him, despite opposition. There is justification for Father Christmas’s inclusion precisely because of the incarnation in our reality, because of the cross-cultural relationship between Narnia and our world, but also because his presence is essential to the doctrine of atonement we can read from the Narniad. An explanation is framed by identifying reasons within the coherence and rationality, the lucidity and consistency, of Lewis’s creation, not by generating allegorical connections. Lewis’s Platonic Idealism is the key to the inclusion of this Narnian gift-bearer (the name “Father-Christmas” is taken into Narnia by the humans, along with personified evil—Jardis—and the ability to sin). In this framework we can explicate a coherent reason and justification within the context of Narnian atonement theory; as such this Father-Christmas-type-gift-bearer is an eschatological harbinger of the loving judgement of God: the Aslan-Christ’s ultimate gifting of himself to redeem his creation.

Download this essay in PDF:

PDF :: C.S. Lewis–On The Christ of A Religious Economy. I. Creation and Sub-Creation.

If citing this essay please use the following:

P.H. Brazier, ‘C.S. Lewis–On The Christ of a Religious Economy. I. Creation and Sub-Creation’

www.cslewisandthechrist.net/csl_on_the_christ_of_a_religious_economy_1.html.

and then give paragraph numbers and date accessed

PDF:

On The Christ of a Religious Economy

I. Creation and Sub-Creation.

Each chapter is subdivided into multiple sections

and sub-sections. Click here for a detailed contents :

PDF : C.S. Lewis - On The Christ of A Religious Economy

I. Creation and Sub-Creation

Home

Book One

Book Two

Book Three

Book Four

Links

Contact

“In the Highest Degree”

Author